Posit Newsletter #04

Ends of the World / A Paradise Built In Hell

The Sun Also Sets

The theme for this issue of Posit is 'ends of the world'. Themes are rather loose in this newsletter, but they certainly help to organize my thinking and the material I gather. In this case, I think it adheres quite well, and maybe that has as much to do with the news as with any curatorial success on my part.

We're at war, again, and it appears to be occuring a truly terminal time for the world as we've known it. In Munich, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio recently declared an end to the 'old world order' of international law, and the renewal of "Western Civilization's" dominance and ascent. In essence, he, like Stephen Miller, are asserting a return to the age of 'might makes right'. Their idea of a thousand year reich is absurd, of course; the decline of western hegemony is clear, as is the destabilization of the climate, both are evidence of an unsustainable course. A few hundred years of industrial and technological progress—enacted through colonial violence and environmentally devastating extraction—is not the basis for an enduring future of the sort the fascists promise.

A key part of my project here is to explore how the past offers a better lens for picturing the future than the promises of industry or science fiction. It's become something of a pop-heuristic, but the so-called Lindy effect demonstrates that the longer something has persisted the longer it is likely to remain. Besides being hyper violent, extractive, wasteful, inequitable, and volatile, the systems of modern industrial capitalism are also relatively new; it is therefore not prudent to suggest they'll persist for much longer. To me, this is a relief; a shift away from what we may call the "Western way" is an 'end of the world' that I would honestly welcome (which is not to endorse any other superpower that may rise or be rising in the meantime).

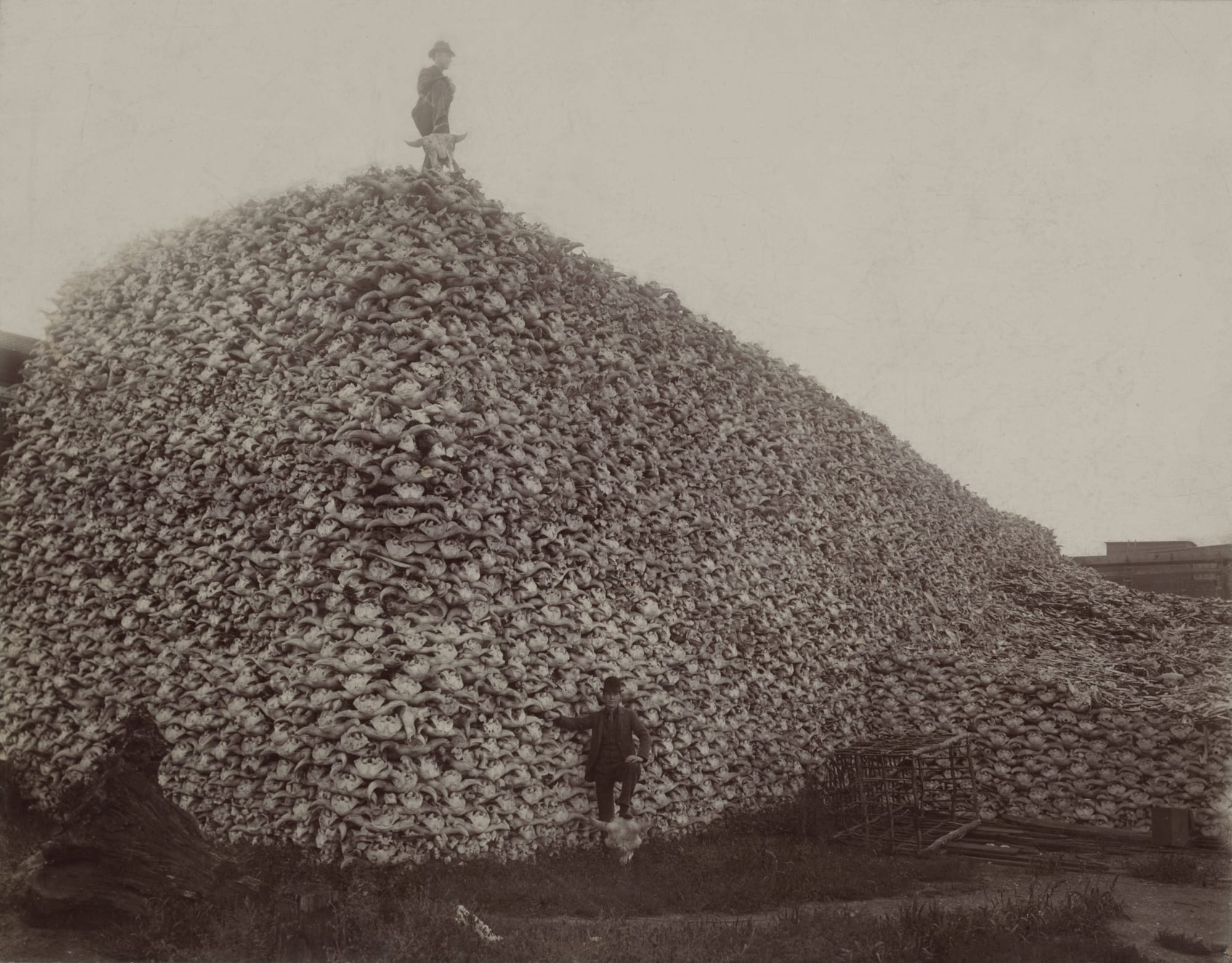

It is worth remembering that the 'end of the world' is nothing new. Indigenous people, it is said, have experienced the apocalypse many times over. "Globally, Indigenous people have already experienced the end of the world," writes cultural critic Sharon Arnold. "The end of Western civilization isn't relevant to Indigenous futures—the end of the settler’s world is not the end of the Indigenous world—and the second invasion or apocalypse is only the second to Indigenous People. For settlers, it is the first."

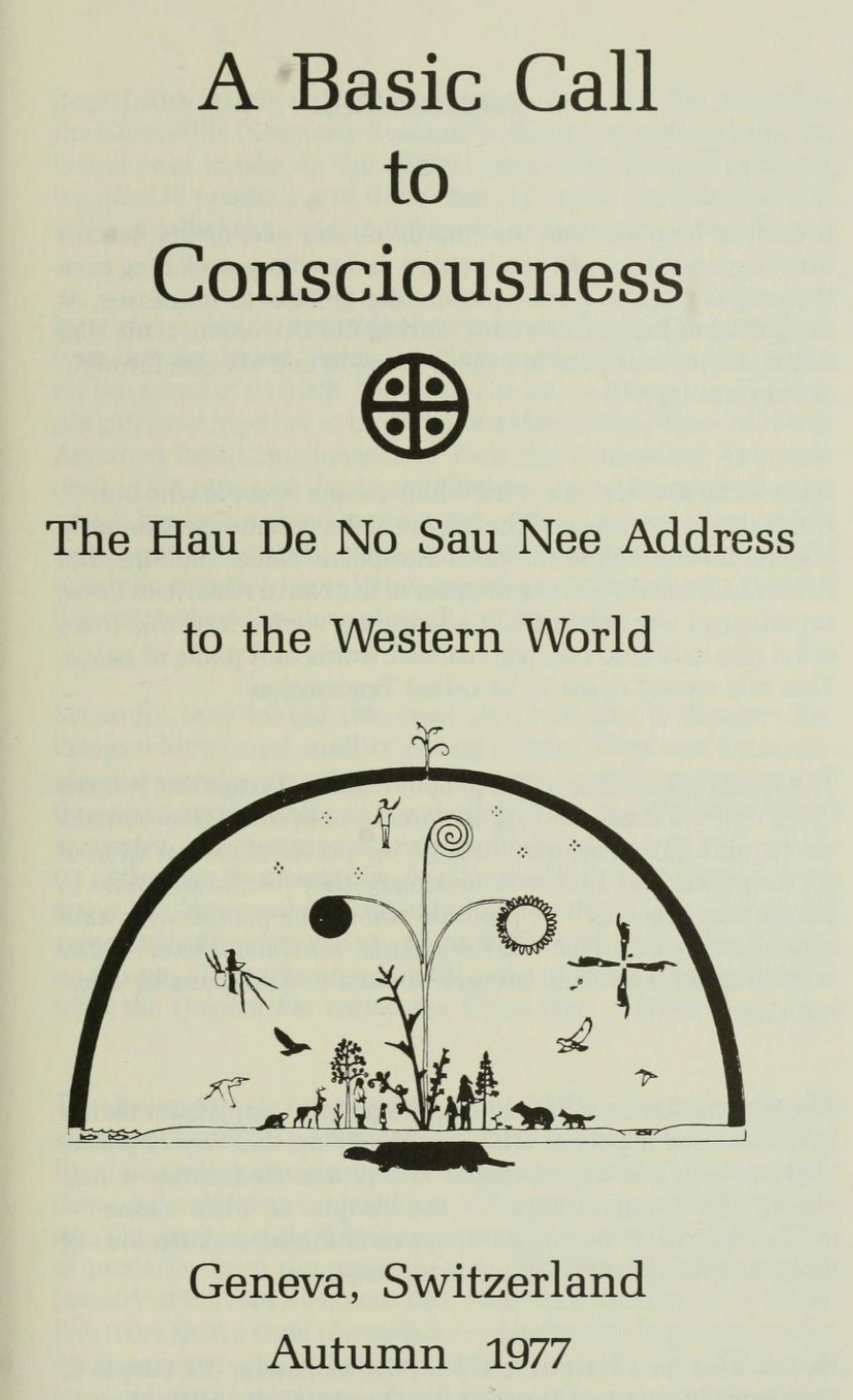

As part of looking into Indigenous futures, and the notion of worlds that have already ended, I read the Haudenosaunee's Basic Call to Consciousness; submitted to the UN in 1977, it is a statement of persistence and resilience, as well as a pointed critique of western civilization that is deeply resonant today. I wrote about it here:

On a related note, I also wrote about an exhibition I caught at the Metropolitan Museum of Art at the end of last year. It wasn't an official exhibition, but a kind of guerilla intervention upon the Met's American Wing, an assertion of continued existence by the Indigenous peoples erased in the landscapes and heroics centered by so many works in the gallery. I wrote about it here:

In the historical timeframe, worlds end all the time. We all live in the wreckage of countless lost worlds, some we can know in retrospect, many we’ll never see or understand. It’s natural for orders to end, and inevitable for those that are unsustainable or inequitable. This is a lesson I’ve been trying to integrate at the personal level—in personal patterns or relationships that are structurally unsound—while I also strive to accept it at the level of the society of which I’m part.

Part of what helped crystallize this thought for me was a recent talk given by Berne Sanders, in which he took as read the narrative that AI and robotics are imminently and inevitably going to transform the world in a way that makes the Industrial Revolution seem trivial. That may in fact be true, and in hearing the old man speak, I wondered if my analysis gave short shrift to such developments. However it also reminded me that the fundamentals of what defines a decent future will remain the same whether robots take all our jobs or not. Namely, a future based on reciprocity, stewardship and repair, with the Earth, to one another, and to the deep roots that the present shares with the past. In other words, regardless of what happens in the worlds of industry and innovation, our collective task remains the same, and it is the same task that has been centered by Indigenous peoples and all manner of activists and artists and alarmists for generations, ever since the project of industrial capitalism began reshaping the face of the planet, and long before.

What remains when the world ends? The world itself. Life, the flowing of water, the patience of stones. The worlds most prone to ending are the ones we humans build, and the more those worlds we build accord with nature, the more durable and regenerative they will be.

Further Reading:

At Noema, Julian Sayarer takes a ride on the sail freighter Tres Hombres, thoughtfully exploring the question of the role of technology, the liberty in limitations, and the radical possibility of realizing an idealist’s vision of the future:

Relatedly, at the Guardian, Damian Carrington reports on how the economic modeling of climate change impact have been limited to rising temperatures, missing the potentially irreversible consequences of tipping points that could undermine the entire global economy. “We can’t bail out the Earth like we did the banks.”

Also at The Guardian, Matthew Taylor reports on UN secretary general António Guterres’s embrace of what amounts to a degrowth principle, moving beyond GDP as a measure of economic success, and instead center human wellbeing, ecological sustainability, and equity:

More on the academic side, author Alyssa Battistoni is interviewed on her new book, Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nature, about the Marxist understanding of nature and the ‘services’ it provides:

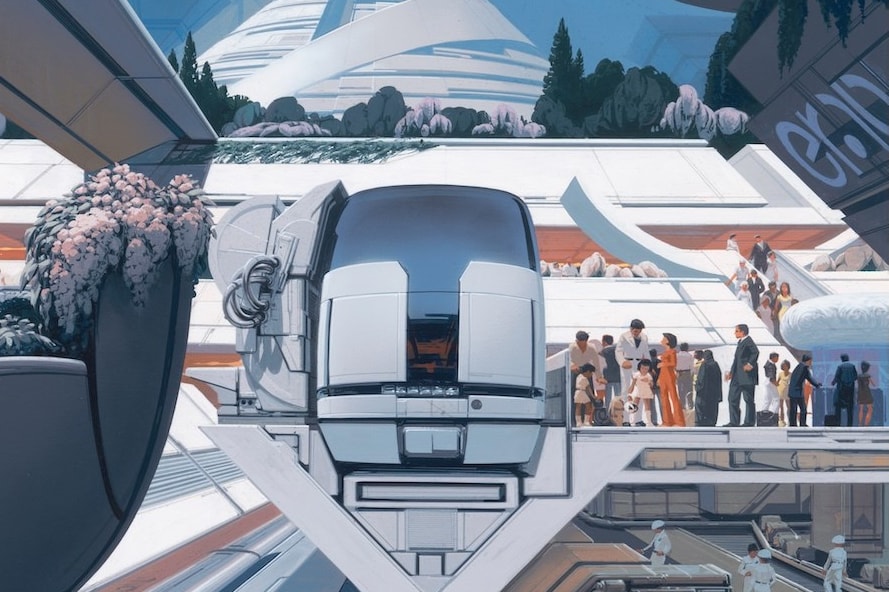

For Dazed, Thom Waite takes the visionary work of Syd Meade as a jumping point for exploring so-called ‘bright futurism’ and the question of what role optimism plays in picturing—then realizing— a better tomorrow:

Lots of good stuff at the Guardian this month, including this long read about the misunderstood history of the Maya, both the extent and diversity of the civilization, as well as how it ended, with implications for the understanding of how the state builds power on a hijacked understanding of history:

At WIRED, Boone Ashworth introduces the efforts of various makerspaces to equip activists and rapid responders—with 3D printed whistles, mesh network communications, and more—in dealing with the mounting threat ICE poses to their communities:

At the New York Times Magazine, T.M. Brown addresses a thought I’ve had for some time: that we’re on track for the Paul Verhoeven version of the future (and that’s not a good thing):

In case you don’t have a NYT subscription (and why would you?) the article is archived here: https://archive.is/lSOrC

Parting Thought

Over the last few weeks, I've been revisiting Rebecca Solnit’s A Paradise Built in Hell, which documents examples of how the best of humanity tends to emerge under the worst circumstances. As conditions get worse, globally and locally, it gives me hope to think the better angels of our collective nature will rise to meet the challenge. Below are two short excerpts from the book, maybe worth keeping in mind as we continue absorbing news of a war abroad and the increasingly tangible realities of fascism and climate change and other disasters mount.

Disasters are, most basically, terrible, tragic, grievous, and no matter what positive side effects and possibilities they produce, they are not to be desired. But by the same measure, those side effects should not be ignored because they arise amid devastation. The desires and possibilities awakened are so powerful they shine even from wreckage, carnage, and ashes. What happens here is relevant elsewhere. And the point is not to welcome disasters. They do not create these gifts, but they are one avenue through which the gifts arrive. Disasters provide an extraordinary window into social desire and possibility, and what manifests there matters elsewhere, in ordinary times and in other extraordinary times.

Two things matter most about these ephemeral moments. First, they demonstrate what is possible or, perhaps more accurately, latent: the resilience and generosity of those around us and their ability to improvise another kind of society. Second, they demonstrate how deeply most of us desire connection, participation, altruism, and purposefulness. Thus the startling joy in disasters. ... The joy in disaster comes, when it comes, from that purposefulness, the immersion in service and survival, and from an affection that is not private and personal but civic: the love of strangers for each other, of a citizen for his or her city, of belonging to a greater whole, of doing the work that matters.